- Home

- J. G. Ballard

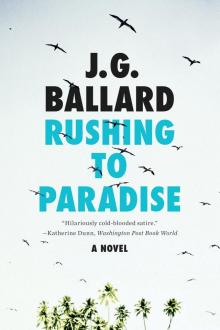

Rushing to Paradise Page 5

Rushing to Paradise Read online

Page 5

Neil promised vaguely that he would help, but he had secretly ided not to join the expedition. Television and press re visiting the shrimp-trawler in Honolulu harbour, describing in provocative detail the preparations for the ecological sea-raid on a military outpost of the French colonial empire. The Defence Ministry in Paris neither confirmed nor denied that nuclear tests were to re-start on Saint-Esprit, but warned that any unauthorized vessel entering the exclusion zone would be boarded and seized.

Neil returned to a quixotic mission of his own, the marathon swim across the Kaiwi Channel. The months in hospital had softened the muscles of his legs and shoulders, and his first twenty lengths in the university pool left him too exhausted to climb from the shallow end. Weeks of intense body-building and pool practice would be needed to return him to fitness.

Rising at six, determined to work himself back to a hundred lengths a day, he tried not to think of Dr Barbara, Saint-Esprit or the albatross.

But memories of the disbarred physician and her passionate breath tugged like the waking nerves in his injured foot, distracting him as he mapped the currents of the Kaiwi Channel on the U. S. Navy charts. Curious to see her before she sailed, and aware that he might never meet her again, he decided to drive to the harbour to say his goodbyes. The revelation that she had killed her elderly patients lay in the back of his mind like an old newspaper in an attic, fading in a moral climate that took a more tolerant view of euthanasia and, tacitly, even approved of the process. Few of her new-found admirers had lost faith in her or stepped back for a moment to ponder her multiple murders.

Paris-Match now lauded the transformation of ‘Dr Death’ into ‘Dr Life’. All lives were precious, but the albatross and manatee now outranked the lowly human being.

Moreover, Neil knew, he missed Dr Barbara, her strong will and her disconcerting coarseness and affection. He remembered how she bullied him during the voyage to Saint-Esprit, while her fingers forever ran across his chest, reading the braille of some invisible desire in his urgent skin. He thought of the thuggish French marines with their rubber truncheons, and wondered how to dissuade her from sailing to the atoll.

On the first Sunday after leaving the hospital he parked the jeep near the

harbour and hid himself among the strolling tourists. The Dugong was moored beyond the inter-island ferry station, high bows already pointing towards the open sea. On a steel platform below the bridge a satellite dish cupped the sky. A military staff car stood on the quay, and men in camouflage fatigues climbed the gangway.

Neil limped forward, pushing between the tourists. He hoped that the American government, under pressure from the French, had decided to impound the vessel before it could set sail. But when he reached the staff car he found a driver with a bandit moustache and shaven head lounging behind the wheel. Trans fers of a dugong, manatee and great white shark were stuck to his neck, and a rondel on the door was emblazoned with ‘Wild Water Kingdom Inc. Live and Love - an Irving Boyd Planetary Project’.

Neil approached the gangway, stepping past a dozen crates packed with tents and camping equipment, cartons of macro biotic and vegetarian food, a portable ocean of bottled mineral water, camera lights and silver umbrellas. Gazing calmly upon all this from the bridge was Captain Wu, the Hong Kong Chinese skipper, a small, trim figure in white shorts, knee-length socks and peaked cap. Beside him was the philanthropist and software genius, pale eyes taking in every detail through his over-large spectacles. He noticed Neil standing uncertainly at the foot of the gangway and gave a gentle wave, like an absent minded pope extending his benediction.

‘Neil, don’t fall in!’ Dr Barbara stepped from the cabin below the bridge.

She waited by the gangway and caught his arm when his numbed foot missed a worn rubber cleat. She pulled him onto the deck, surprised but glad to see him, weighing the stronger muscles of his arms like a farmer’s wife pleased with the growth of a prize bullock.

‘Neil, we’ve all missed you. Are you coming with us?’

‘Dr Barbara, I wanted to -‘

‘Good. I knew you would.’ Dr Barbara stood back and then embraced him fiercely, strong hands searching his rib-cage and shoulder blades, reassuring herself that the bones of old still lay within the newly confident muscle. ‘We couldn’t have gone without you.’

‘Dr Barbara…’ Neil wiped her gaudy lipstick from his forehead. ‘What about the French navy? They’re waiting for you…

‘Don’t worry! There’s a new wind blowing.’ She consulted her roster. ‘We’ll find a cabin for you later, but first I want you to meet Monique Didier, our very special new friend.’ She put an arm proudly around Neil as a vigorous, dark-haired woman in white overalls stepped onto the deck below the bridge and emptied a waste-bucket of soapy water into the sea.

‘Monique is a chief steward with Air France,’ Dr Barbara told him. ‘But she’s given everything up to join us. Monique, this moody chap is Neil Dempsey, champion swimmer and my right-hand man.’

‘So… of course, I saw you on TV. You’re practically a film star.’ The Frenchwoman bowed steeply, holding Neil’s hand as if touching an icon. ‘I know all about your trip to Saint-Esprit.

You’re really my hero.’ Despite her ironic tone, Neil found himself reddening again.

During her hospital visits Dr Barbara had often described this high-principled air hostess. Now in her late thirties, Monique Didier was the daughter of one of France’s first animal rights activists, the writer and biologist Ren

�

Didier. She and her father had set up a wild-life sanctuary in the Pyrenees for an endangered colony of bears. For years they endured the abuse and hostility of local farmers angered by the bears’ sheep-killing and their sentimentalized image in the metropolitan press. All this had made Monique prickly and defensive, but she was dedicated to her campaign, brow-beating her first-class passengers on the Paris-New York and Paris-Tokyo runs. After repeated warn ings, Air France had lost patience and sacked her.

Neil was already wary of her sharp tongue, but Monique seemed genuinely reassured by his arrival. He was tired after walking along the crowded quay, and wanted to sit on the platform of the satellite dish, but she hovered around him as

if eager to fasten his seat-belt and slip a plastic tray onto his lap.

‘It’s excellent that you’re coming,’ she told Neil, still sizing him up. ‘We have to get ashore very quickly, and you know the secret pathways to the airstrip.’

‘They’re not really secret…’ Neil realized that Dr Barbara had been busy mythologizing the island. ‘What about Kimo?’

‘He’ll be with us, of course. But we must take care not to expose him.’

Monique rattled her bucket with a show of distaste.

‘Those French officers are so racist. One chance and they’ll shoot hiiii down like a pig.’ They shot me.’

‘But not again!’ Monique’s eyebrows bristled. ‘You’re an emblem, Neil. The TV

screen is your shield, no bullet can pierce you. Is that right, Barbara?’

‘Of course, Monique, though I wouldn’t put it quite like that.’! Dr Barbara tried to pacify her. ‘Let’s hope no-one gets shot.’ The endless bedside interviews and television appearances had done their work, Neil reflected. He was now a talisman of the animal rights movement, to be carried shoulder-high like the stuffed head of a slaughtered bison. When Dr Barbara took him onto the bridge she introduced him with a flourish to Captain Wu and Irving Boyd, as if his appearance guaranteed her own credentials.

The computer entrepreneur greeted him with a grave bow, eyes slowly blinking behind the thick lenses like an ever-wary alarm detector.

‘We prayed for you, Neil,’ he said in a soft Texan voice, to which he listened as if the words contained a concealed code.

‘When you were shot the planet held its breath. I think even the nianatees and the dugongs prayed.’

‘I prayed for the albatross, Mr Boyd.’

‘Everyone prayed fo

r the albatross. Meanwhile, I hope you take part in the sanctuary island project.’

‘No-one’s asked me-is that a TV series?’

‘Irving means Saint-Esprit,’ Dr Barbara pointed out. ‘I think we can look forward to some awfully high ratings.’

‘We want you there, Neil.’ Boyd’s eyes were fixed on Neil with all the humility of a film producer discovering a face of Christ-like pathos among a crowd of extras. ‘There’s a starring role for you.’

‘Well, maybe… I don’t know much about acting. I’m still coping with reality.’

‘Reality? That’s a public service channel, Neil. I’m planning to put up the first privately operated ecological satellite. We’ll beam you and Dr Barbara into every home on the planet..

As Boyd outlined his prospectus it was clear to Neil that the entrepreneur saw the expedition to Saint-Esprit as little more than the reconnaissance for a television programme. But Dr Barbara bundled him down the stairway before he could reply.

‘For God’s sake, Neil! He’s lent us the ship.’ Neil was pleased to see her annoyed with him. A few minutes in Dr Barbara’s presence was more of a tonic than all the hundreds of lengths in the university pool.

‘The Dugong’s a stage-set, Dr Barbara. Like the replica of the Bounty. For him everything turns into television.’

‘Maybe, but he still controls the off-switch. Now meet Professor and Mrs Saito. And no jokes about atom bombs.’ A young Japanese couple broke off their work in the galley to bow to Neil. Both professional botanists, they had flown in from Tokyo the previous day after abandoning their careers at the University of Kyoto and placing themselves at the service of Dr Barbara’s vision. They had brought with them two small suitcases, a plastic tent and a set of folding chairs, like overgrown children about to play on a holiday beach. They treated Neil to a pair of synchronized smiles that had scarcely faded when he left the Dugong an hour later, promising Dr Barbara to return and help with their preparations for departure.

Trying to make sense of this naive but muddled crew, Neil drummed his forehead so fiercely against the jeep’s steering wheel that he bruised the skin.

Already he knew that some way had to be found of preventing Dr Barbara and her ship

of fools from ever leaving Honolulu.

During the next days, as he swam his lengths, he listened to the pool-side radio. Media interest in the Dugong remained high, prompted by the immense white wings which Kimo had painted along the trawler’s hull. Already a novelty designer in Waikiki had turned the striking image of wave and wing into a natty series of badges and lapel buttons.

Every afternoon Neil drove to the harbour, hoping to find that French agents had scuttled the ship. Dr Barbara was usu ally absent, lobbying the French consulate with a party of sympathizers and addressing the last fund-raising rallies. Captain Wu and his seven Filipino crew continued to load the stores, fuel and fresh water, watched by the solitary figure of Irving Boyd, brooding between the white wings of the ship like Poseidon lost in a dream of his oceans.

A group of New Age hippies carrying an anti-vivisectionist banner had taken up residence on the quay. Shaking their tam bourines, they danced among the stall-holders selling balloons and environmentalist geegaws to the tourists. Even Irving Boyd stirred from his meditations and tapped the air to the cheerful rhythm. He invited the troupe onto the bridge, where they danced around a bemused Captain Wu and then conducted a gentle mock-religious rite beside the satellite dish.

Watching this antic ship and its antic crew, Neil was sure that they would never leave port. But a week after his meeting with Dr Barbara he met the latest volunteers to join the expedition and realized that the Dugong would not only set out from Honolulu but had every chance of sailing straight into the French guns.

A film crew of three -Janet Bracewell, the Australian director, and the cameraman, her American husband Mark, together with the Indian sound-recordist, Vikram Pratap - were to be Irving Boyd’s ambassadors to Saint-Esprit. Detached from the Wild-Water sanctuary, they would record the progress of the expedition and transmit live pictures of any hostile French action to Boyd’s TV station in Honolulu and from there to the world’s watching networks. Already they were filming the re porters and animal rights activists who roamed the Dugong, interrupting the work of the Filipino crewmen and earnestly questioning them about their attitudes to nuclear testing and the environment.

Incited by the camera’s presence, the visitors turned the shrimp-trawler into the venue of a continuous party. Passers-by pilfered the unloaded stores and helped themselves to the bottles of donated wine. By the time Dr Barbara and Monique returned in the evening they found tourists dancing on the quay to the New Age tambourines, eco-banners floating on the cool harbour air and an amiable wraith of pot-smoke lifting through the Chinese lanterns. Delighted by this festive atmosphere, Dr Barbara danced with Monique while Captain Wu paced his darkened bridge and a disapproving Kimo sat with his paint store in the high bows of the Dugong.

But Kimo was not alone in being puzzled by Dr Barbara’s failure to control her sympathizers. As he watched from the pier of the inter-island terminal Neil had noticed a tall, white haired American in his early forties standing beside his rented car on the quay. Driven by his wife, he usually arrived in mid afternoon, stepped from his seat and spent an uncomfortable hour gazing at the ship. The sight of the unguarded stores and the three inflatables on their trailer seemed to unsettle him. While his wife sat stoically at the wheel he would pace around the rubber craft, wiping the wine-stains with his handkerchief, and only relaxing when the Filipinos finished their interviews and returned to work.

Sometimes he would shout at the milling tourists, and then break off to practise his tennis backhand, sweeping his long arm in a compulsive way, as if trying to land a difficult shot in his opponent’s court.

Neil assumed that he was forcing himself to decide whether or not he should join Dr Barbara. On his fourth visit to the quay, the American saw her arrive after her last day’s work at the children’s home. He avoided her eyes when she strode past, leaned his elbows on the window sill of the car and stared at his patient wife. Before she could speak he turned with a nervous tic of his shoulders and followed Dr Barbara to the Dugong, counting her steps aloud to himself. Holding his

arms above the heads of the Japanese tourists, he climbed the gangway, his eyes clear and all his doubts apparently resolved.

Neil soon learned that this was David Carline, the last volunteer to join the expedition. The president of a small pharma tical company in Boston, he had been on holiday in Honolulu w n he learned of Dr Barbara and her mission to save the albatross. The family firm had for decades supplied its pharmaceuticals to the third world, and Canine had frequently taken leaves of absence to join American missionary groups in Brazil and the Congo, teaching in mission schools and delivering lay sermons at the open-air church services. Intelligent, rich and eager for hard work, he was the first sane presence on board the Dugong.

Neil disliked him on sight. From the moment that Canine came on deck, swinging his expensive, travel-worn suitcase up the gangway, Neil was certain that he would restore order to the ship, concentrate Dr Barbara’s wayward mind and see that the trawler set sail as planned. Sure enough, within little more than a day Carline had assumed the deputy leadership of the expedition.

Both Monique and Dr Barbara were glad to defer to someone with the management skills needed to restore order to the crates heaped chaotically in the forward hold. Captain Wu welcomed him to the bridge, recognizing a fellow spirit, and Irving Boyd happily ceded his place to Canine and returned to his television station in Honolulu.

Carline soon set about trimming the ship. First he persuaded the Bracewells to save their film footage, and affably suggested that they join the other expedition members in the job of winching the silver-skinned inflatables from their trailer on the quay. Once the camera vanished from the scene many of the tourists and New Agers drifted away, taking the stall-ho

lders with them. The work of loading stores resumed, and Kimo descended from his perch, eager to support Canine’s brisk new regime.

Carline greeted Neil with a testing handshake, sensible enough to ignore the English youth’s hostility.

‘Neil, you’re the reason I’m here, all the way from Boston.

We’re proud of you and everything you did on Saint-Esprit.’ He gestured to Mrs Carline, sitting sombrely in the car parked by the gangway. ‘Even my wife respects you -a great deal more than she respects me, I can tell you. I’d like you to meet her, she admires your guts in sailing to Saint-Esprit and taking on the Fre It might help her to understand why I had to join you.’ y did you join?’

‘Hard to say, Neil. I guess I need to go to Saint-Esprit to find out. Of course, I want to save the albatross, but there’s more to it than that. In a sense I want to save Dr Barbara. The world needs people like her, people with conviction and faith in the rest of us.

For so long we’ve behaved as if we’re all about to leave the planet for good, as if the Earth was some kind of dying resort area. We need more Saint-Esprits. I saw you and Dr Barbara on the TV news and, do you know, I left the hotel and drove straight down here. Anyway, enough of me. Are you fit for work? Kimo’s keen to get the outboards loaded.’ For the rest of the day, as they settled the heavy motors in the hold, Neil kept a careful watch on the American, a nightmare come-true of integrity and good humour. He reminded Neil of the chaplain at his boarding school in England - always eager and understanding, always ready to make the first rugby tackle on the practice pitch. The chaplain had resigned after an affair with the sports master’s wife, and already Neil saw Carline as his chief rival for the attention of Dr Barbara.

High-Rise

High-Rise The Drowned World

The Drowned World The Unlimited Dream Company

The Unlimited Dream Company Running Wild

Running Wild The Day of Creation

The Day of Creation The Wind From Nowhere

The Wind From Nowhere The Complete Short Stories, Volume 2

The Complete Short Stories, Volume 2 Concrete Island

Concrete Island Empire of the Sun

Empire of the Sun The Kindness of Women

The Kindness of Women Vermilion Sands

Vermilion Sands Super-Cannes

Super-Cannes Millennium People

Millennium People The Complete Stories of J. G. Ballard

The Complete Stories of J. G. Ballard Crash

Crash The Drought

The Drought The Atrocity Exhibition

The Atrocity Exhibition The Complete Short Stories: Volume 1

The Complete Short Stories: Volume 1 Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton: An Autobiography

Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton: An Autobiography Rushing to Paradise

Rushing to Paradise Chronopolis

Chronopolis Cocaine Nights

Cocaine Nights High Rise (1987)

High Rise (1987) The Complete Short Stories

The Complete Short Stories The Day of Creation (Harper Perennial Modern Classics)

The Day of Creation (Harper Perennial Modern Classics) The Crystal World

The Crystal World