- Home

- J. G. Ballard

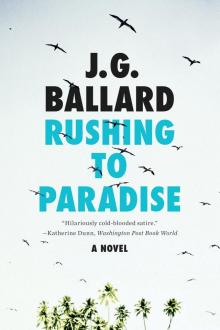

Rushing to Paradise

Rushing to Paradise Read online

Rushing to Paradise

By J.G. Ballard

First published in 1994

PART I

Saving the Albatross

‘SAVE THE ALBATROSS…! Stop nuclear testing now…

Drenched by the spray, Dr Barbara Rafferty stood in the bows of the rubber inflatable, steadying herself against Neil’s shoulder as the craft swayed in the skittish sea. Refilling her strained but still indignant lungs, she pressed the megaphone to her lips and bellowed at the empty beaches of the atoll.

‘Say no to biological warfare…! Save the albatross and save the planet…

A passing wave swerved across the prow, and almost struck the megaphone from her hand. She swore at the playful foam, and listened to the echoes of her voice hunting among the rollers.

As if bored with themselves, the amplified slogans had faded long before they could reach the shore.

‘Shit! Neil, wake up! What’s the matter?’

‘I’m here, Dr Barbara.’

‘That’s Saint-Esprit ahead. The albatross island!’

‘Saint-Esprit?’ Neil stared doubtfully at the deserted coastline, which seemed about to slide off the edge of the Pacific. He tried to muster a show of enthusiasm. ‘You really brought us here, doctor.’

‘I told you I would. Believe me, we’re going to stir things up…’

‘You always stir everything up…’ Neil moved her heavy knee from the small of his back and rested his head against the oil-smeared float. ‘Dr Barbara, I need to sleep.’

‘Not now! For heaven’s sake…

Already irritated by the island, which she had described so passionately during the three-week voyage from Papeete, Dr Barbara raised two fingers in a vulgar gesture that shocked even Neil. Between the lapels of her orange weather-jacket the salt water sores on her neck and chest glared like cigarette burns. But her body meant nothing to the forty-year-old physician, as Neil knew. For Dr Barbara the polluted water tanks of the Bichon, the antique ketch that had brought them from Papeete, their meagre rations and sodden bunks counted for nothing.

Albatross fever was all. If Saint-Esprit, this nondescript atoll six hundred miles south-east of Tahiti, failed to match her expectations it would have to reshape itself into the threatened paradise for which she had campaigned so tirelessly.

‘Reef, Dr Barbara! Time for quiet… I need to hear the coral.’ Behind them was the Hawaiian helmsman, Kimo, his knees braced against the sides of the inflatable as he woi ed the double bladed oar. He sat like a rodeo-rider across the

�

outboard engine, which he had tipped forward to spare the propeller. Neil watched himjockey the craft among the running seas, feinting through the gusts of spray.

For a son of the islands, Neil reflected, Kimo was surprisingly hostile to the ocean. The sometime Honolulu police man seemed to hate every wave, sinking the sharp blades into the swelling bellies of black water like a harpooner opening a dozen wounds in the side of a drowsing whale.

Yet without Kimo they could never have carried out this protest raid on Saint-Esprit. The disused nuclear-test island was a junior and more accessible cousin of the sinister Mururoa, which Dr Barbara had wisely decided to leave alone.

Captain Serrou, the Papeete fisherman, was waiting for them in the Bichon, two miles out to sea. He had refused to join the run ashore, taking Dr Barbara’s talk of chemical warfare agents and imminent nuclear explosions all too literally. Only Kimo had the nerveless skill and brute strength to steer the inflatable through the reef and find an inlet among the deceptive calms that floated a few feet above a

‘We’re drifting Dr Barbara clambered over Neil and tried to seize the Hawaiian’s oar. The inflatable had lost headway, bows wavering as it fell back on the rising sea. ‘Kimo -don’t give up now..

‘Hang on, Dr Barbara… I’ll get you to your island.’ As Dr Barbara shielded the megaphone from the spray, Neil gripped the waterproof satchel that held her tools of trade.

Needless to say, Dr Barbara travelled without any medical equipment. Instead of the hypodermic syringes and vitamin ampoules that would have cleared the ulcers on their lips, or even a roll of lint to bandage a wounded albatross, there were aerosol paints, a protest banner, a machete, and a video-camera to record the highlights of their raid. The television stations in Honolulu, if not Europe and the United States, might well be intrigued by the filmed material and its emotive message.

‘She’s coming, Dr Barbara. ‘Kimo bent his back and drove the craft forward, a mahout of the deeps urging on a reluctant steed.

Listening to the spurning air above the coral towers, he had found an inlet through the reef, a narrow gulley which the French engineers had cut with underwater explosives. Wider and less hazardous channels crossed the southern rim of the atoll, the route taken by the naval vessels supplying the military base. But the open lagoon exposed any unwelcome visitors to the soldiers guarding the island, who would be standing on the beach ready to throw them back into the surf, as the anti-nuclear protesters landing on Mururoa had discovered. Here, on the dark north coast, they could slip ashore unseen, giving Dr Barbara time to find the threatened albatross and rally the full force of her indignation.

Oar raised, Kimo ignored a black-tipped shark that veered past them, chasing a small blue-fish. He waited for the next swell, and propelled the inflatable through the whirlpool of foam and coral debris that erupted as the trapped air burst from the gasping walls. The reef fell away, slanting across the cloudy depths like the eroded deck of an aircraft carrier. They entered the quiet inshore waters, and Kimo fired the outboard for the final six hundred-yard dash to the beach.

‘Kimo… Kimo…‘On her knees in the bows, Dr Barbara murmured the Hawaiian’s name, reproving herself for any fears that his commitment might falter. Neil had never doubted Kimo’s resolve. During the voyage from Papeete the large, stolid man had kept to himself, sleeping and eating in an empty sail-locker, preparing for the confrontation that lay ahead. He always deferred to Dr Barbara, stoically enduring the ecological harangues with which she greeted every unfamiliar bird in the sky, and clearly regarded the sixteen-year-old Neil Dempsey as little more than her cabin boy. Kimo had sunk his savings into their air-fares from Honolulu and the charter of the Bichon, but at times, as he fiddled with the ketch’s radio, Neil suspected that he might be a French agent, posing as a defender of the albatross in order to keep watch on this eccentric expedition.

Eight days out of Papeete they passed a fleet of Japanese whalers, escorting a factory ship that left a mile-wide slick of blood and fat on the fouled sea. The spectacle so appalled Dr Barbara that Neil held her around the waist, fearing that the deranged physician would leap into the bloody waves. As they wrestled together, cheeks flushed by the reflected carmine of the sea, the pressure of Neil’s hands on her muscular buttocks seemed almost to excite Dr Barbara, distracting her until she pushed him away and shouted a stream of obscenities at the distant Japanese.

Kimo, however, had been eerily calm, soothed by the thousands of sea-birds feasting on the whale debris. During the last days of the voyage he sacrificed his own rations to feed a solitary petrel that followed the ketch, even though Dr Barbara warned him that he was becoming anaemic.

He fed the birds and, Neil liked to think, dreamed their dreams for them. In Kimo’s mind the freedom of the albatross to roam the sky deserts of the Pacific had

merged with his hopes of an independent Hawaiian kingdom, rid forever of the French and American colonists with their tourist culture, shopping malls, marinas and pollution.

It was Kimo who told Dr Barbara that the French nuclear scientists were returning to Saint-Esprit, which they had abandoned in the 19705 as a possible testing-ground after moving to

Mururoa, an atoll in the Gambler Islands safely remote from Tahiti. The two hundred native inhabitants of Saint-Esprit had already been relocated to Moorea, in the Windwards, and the island with its camera-towers and concrete bunkers lay un disturbed during the long years of the nuclear moratorium.

However, the threat of a new series of atomic tests had failed to inspire Dr Barbara, a veteran of the protest movements who was helping to run a home for handicapped children in Hon olulu. This restless and high-principled English physician was bored by the endless rallies against ozone depletion, global warming, and the slaughter of the minke whale. But Kimo also informed her that the French engineers on Saint-Esprit had extended the military airstrip, destroying an important breeding ground of the wandering albatross, the largest of the Pacific sea birds.

Saving the albatross, Dr Barbara soon discovered, held far more appeal -for the public. The great white bird stirred vague but potent memories of guilt and redemption that played on the imaginations of the University of Hawaii graduate students who formed her protest constituency. Coleridge’s poem, she often reminded Neil, was the foundation-text of all animal rights and environmental movements, though she was careful never to quote the familiar verses.

Now that they had arrived at Saint-Esprit, where were the albatross? As they coasted towards the beach a flock of boobies circled the inflatable, a hooligan vortex visible to any French patrol boat five miles away. They mobbed the rubber craft, soaring along the wave troughs, beaks lunging at the open sores on Neil’s arms. Dr Barbara thrust the megaphone into their faces, and hopefully scanned the shore for any signs of a hostile reception party. Thriving on opposition, she was always disappointed to be ignored, and aware that she might have to make do with this audience of raucous birds.

The monotonous thudding of the inflatable’s bows against the waves had turned Neil’s stomach. He retched over the side, leaving a few grains of breakfast oatmeal

- an obsession of Dr Barbara’s - on the greasy float. Fending off a persistent booby, he wondered why he had joined the protest voyage. Not only were there no nuclear tests, which he had secretly been curious to see, but there were no albatross.

‘Neil! You’ll be fine when we land.’ Dr Barbara wiped the phlegm from his mouth. ‘Try to hang on - I’m as nervous as you are.’

‘I’m not nervous. Where are the albatross?’

‘They’re here, Neil. I’m sure the French haven’t killed them.’

‘Do we leave if there are no albatross?’

‘There are always albatross.’ Dr Barbara held his head against her shoulder, a proud smile on her chapped lips. Her fading hair was swept back from her high forehead, as if she were deter mined to expose her principled brow to the malign and un scrupulous French. ‘If you look hard enough you can find them.

Now, pull yourself together. We can’t film the landing twice.’ Neil tugged wearily at the satchel. ‘Seriously, doctor, I feel sick. It could be radiation poisoning…

‘Very likely. It’s all that talk about Eniwetok and Mururoa.

I’ve never met anyone who dreamed of nuclear islands.’

‘Save the atom bomb..

‘Save Neil Dempsey.’ Neil allowed her to cuff him. Dr Barbara was able to switch from peremptory schoolmistress to doting mother in a way that always disarmed him. She was forever touching Neil, peering into his eyes and checking his urine as if carrying out a running inventory of his working parts, a calculated appeal to a sixteen year-old’s libido that he could barely resist, whatever its motives. Once, when she hugged him playfully in the galley, a slice of sweet potato

between her teeth, he had been tempted to strip naked in front of her.

‘Neil, get ready to start the film. I can smell the French..

Neil slipped the camera from its waterproof case. Kimo had cut the engine, and they rolled with the waves towards the shore, where the palms formed a dense palisade above a beach of black volcanic ash. Dr Barbara threw aside her weather-jacket and stood legs apart in the bows, shoulders squared and blonde hair flying like a battle-standard on the wind.

As always, Neil enjoyed filming her in close-up. Through the viewfinder he could see the exposure sores on her face, and her left nipple extruding itself through the wet cotton of her shirt, an eye-catcher for the television news bulletins or the covers of Quick and Paris-Match. He steadied himself against the float as an overtaking wave eased them from its back, and zoomed in on Dr Barbara’s high nose and determined mouth, wondering if she had been plain or beautiful as a medical student in Edinburgh twenty years earlier.

‘Take lots of film of the island,’ she told him, now directing the documentary of which she was already star and scriptwriter.

‘And get as many birds as you can.’

‘There are no albatross. Only these boobies.’

Neil sucked his numbed fingers and fumbled with the miniaturized controls of the Japanese camera. He had been working as a part-time projectionist at the film school of the University of Hawaii when Dr Barbara recruited him, and despite everything he said to the contrary she instantly convinced herself that he was a skilled cine-photographer. Fortunately the camera refocused itself, and he began to film a panorama of Saint-Esprit. The atoll was a chain of sand-bars and coral islets, the rim of a submerged volcanic crater that enclosed a lagoon five miles in diameter. The largest of the islands lay to the south-west of the lagoon, a crescent of dense forest and overgrown plantations dominated by a rocky mass that rose to a summit four hundred feet above the beach.

Searching for the threatened sea-birds, the great ocean wanderers, Neil panned across the cliffs. The fluted cornices of blue lava together resembled the corpse of a mountain dead for millennia, propped into the sky like a cadaver sitting in an open grave. A tenacious vegetation clung to the exposed chimneys, living wreaths feasting on a set of aerial tombs. No albatross had yet appeared, but a steel tower stood on the summit, its cables slanting through the forest canopy.

The slender lattice was too frail to bear the weight of a nuclear device, and Neil assumed that it was an old radio mast. As they rode the last waves towards the beach he fixed the camera lens on the tower, hoping that its rigid vertical would restrain his stomach before it could climb into his throat. Thinking of the newsreels of atomic tests, he imagined a bomb detonated at its apex, releasing a ball of plasma hotter than the sun. For all Dr Barbara’s passion for the albatross, the nuclear testing-ground Is had a stronger claim on his imagination. No bomb had ever exploded on Saint-Esprit, but the atoll, like Eniwetok, Mururoa and Bikini, was a demonstration model of Armageddon, a dream of war and death that lay beyond the reach of any moratorium.

The stern of the inflatable rose as the last breaker swept them towards the beach. Neil stowed the megaphone and camera in the satchel and sealed the waterproof tapes, bracing himself against the centre bench. Dr Barbara crouched like a commando in the bows, fists gripping the mooring line. Two-bladed oar in his huge hands, Kimo stood astride the engine, holding the craft on the curved shoulders of the wave. The rolling wall crumbled in a white rush that hurled the inflatable onto its side and sent the oar windmilling through the spray.

Bludgeoned by the violent surf, they swam through the waist-deep water as the craft broke free from the sea and slewed across the sand. Carrying the satchel over his head, Neil forced himself against the undertow and waded through the slurred foam. Kimo dragged the inflatable onto the narrow shelf below the palms, and calmed the trembling rubber hull with his massive arms. Dr Barbara retrieved the oar, but a wave struck her thighs, knocking her from her feet. She fell to her knees in the seething water, stood up with her shirt around her waist and seized Neil’s hands

when he pulled her onto the beach.

‘Good chap… are we all here? Where’s the camera?’

‘It’s safe, Dr Barbara.’

‘Hang on to it - the world’s watching us through that little ens…

She sat gasping on the sand beside Neil and wiped the wate

r from her salt-roughened cheeks. Snorting the phlegm from her nostrils, she stared back at the sea, openly admiring its aggres sion. Still breathless, Neil leaned against the coarse sand. After the three-week voyage, the endless yawing and rolling deck, the sheer immobility of the island made him giddy. The black ash was covered with coconut husks, yellowing palm fronds, spurs of pallid driftwood and the shells of rotting crabs. Over every rh1ng hung the stench of dead fish. The sun had vanished behind the forest canopy and a cold spray enveloped the island. A few feet away, through the trees behind them, was an insect realm of high-pitched chittering, dank mist and over-ripe vegetation.

‘Right… time to move on.’ Dr Barbara stood up and shook the water from her shirt. ‘Kimo, it’s up to you to get us out again.’

‘We’ll make it, doctor. I’ll fool the sea for you.’ As the foam surged around his feet Kimo worked on the outboard motor, clearing the sand from the air intakes.

‘We’ll wait for high tide, two hours from now.’

‘Two hours? I hope that’s enough. The French may be having lunch… Now, where’s Neil?’ Neil touched her ankle. ‘Still here, Dr Barbara, I think..

Dr Barbara squatted beside him, buttoning her shirt from his queasy gaze. ‘Of course you’re here. Don’t lose heart, Neil. I need you now - you’re the only one who can work the camera.’ She brushed the damp hair from his eyes and ran her hand over his muscular arms, as if reminding herself that he was still the pugnacious and lazy youth she had met one evening in Waikiki, dreaming of atomic islands and marathon swims. During the voyage from Papeete she had spared him from the more arduous tasks, leaving Kimo to shift the heavy sails and work the bilge pump, and Neil sensed that he was being saved for a more exacting role than that of expedition cameraman.

‘How long do we stay on Saint-Esprit?’ he asked.

‘Long enough to make the film. We can’t help the albatross yet, but we can show people what’s happening here.’

‘Doctor…’ Neil gestured at the deserted beach and the clouds of mosquitoes.

High-Rise

High-Rise The Drowned World

The Drowned World The Unlimited Dream Company

The Unlimited Dream Company Running Wild

Running Wild The Day of Creation

The Day of Creation The Wind From Nowhere

The Wind From Nowhere The Complete Short Stories, Volume 2

The Complete Short Stories, Volume 2 Concrete Island

Concrete Island Empire of the Sun

Empire of the Sun The Kindness of Women

The Kindness of Women Vermilion Sands

Vermilion Sands Super-Cannes

Super-Cannes Millennium People

Millennium People The Complete Stories of J. G. Ballard

The Complete Stories of J. G. Ballard Crash

Crash The Drought

The Drought The Atrocity Exhibition

The Atrocity Exhibition The Complete Short Stories: Volume 1

The Complete Short Stories: Volume 1 Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton: An Autobiography

Miracles of Life: Shanghai to Shepperton: An Autobiography Rushing to Paradise

Rushing to Paradise Chronopolis

Chronopolis Cocaine Nights

Cocaine Nights High Rise (1987)

High Rise (1987) The Complete Short Stories

The Complete Short Stories The Day of Creation (Harper Perennial Modern Classics)

The Day of Creation (Harper Perennial Modern Classics) The Crystal World

The Crystal World